The dire consequences of Iraq’s criminalization of the Baath Party

Subversion of political freedom, opening the floodgates of political targeting and the polarization of Iraqi society

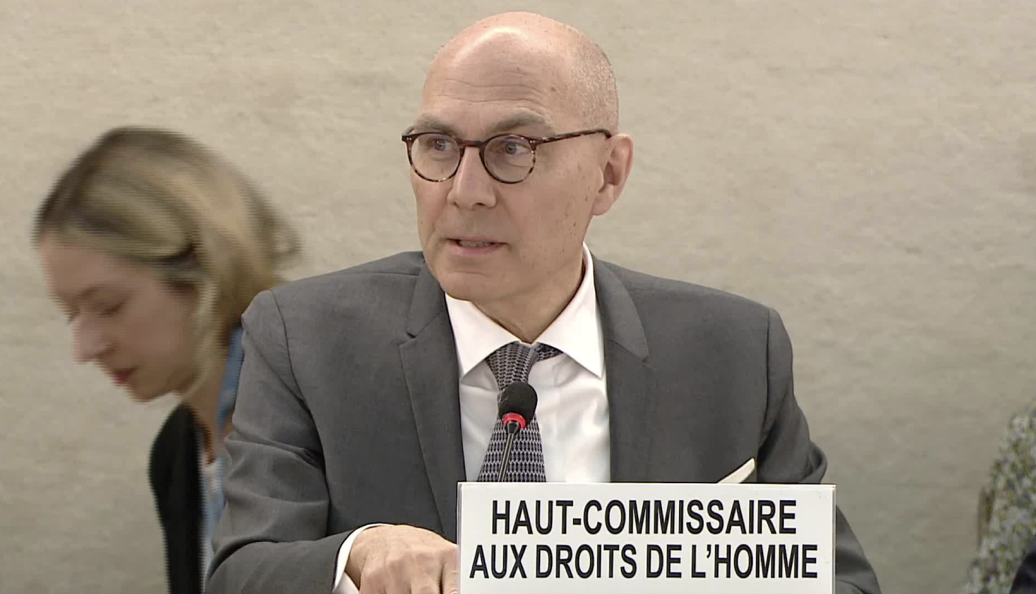

On August 4th, 2016 Geneva International Centre for Justice (GICJ) sent an urgent letter to the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Mr Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein, to express its sincerest concerns about a new bill passed by the Iraqi Parliament on the 30th July, 2016. The decree in question criminalizes the existence of and belonging to the Arab Socialist Baath Party (hereinafter the “Baath Party”) and bans the party and other even remotely similar groups from any political, social, intellectual or cultural activity across the country.

In this regard, GICJ expressed its sincere concern about the enactment of this sweeping law as it violates internationally recognized human rights law in regards to political freedom and participation, has a very real potential to be abused by the government in order to legitimize illegal political targeting, as well as contributes to social and political polarization and violence in Iraq.

In the letter, GICJ provided Mr Ra’ad Al Hussein with an analysis of the history and results of the Baathist purge that began in 2003, an account of the latest developments by the Iraqi legislature, and translations of key Articles of the new bill. Furthermore, in relation to these developments, our correspondence identified crucial areas of concern and provided recommendations for the international community and the relevant United Nations mechanisms and bodies.

The grim history of De-Ba’athification in Iraq

Following the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq and the fall of the government in 2003, the coalition started the implementation of its plan to dismantle the Arab Socialist Baath party (hereinafter “Baath Party”). To do so, the U.S.-led coalition introduced a series of legal and administrative measures that forcefully removed alleged members of the Baath Party from all public sectors. These policies, which were to have profoundly detrimental consequences for Iraqi society, came to be known as ‘de-Baathification’.

|

Those who were subjected to these measures were not individually assessed on the basis of their competence, participation in human rights violations or any other measure of integrity. Instead, based on the assumption that any and all high standing officials must have been ideologically committed to Baathism and thus had committed serious illegal acts, tens of thousands of trained professionals were dismissed from government based solely on their rank in the civil service or Baath Party. Furthermore, some 400,000 thousand conscripts, officials, officers and other from Iraq’s military and security institutions were left unemployed.

This assumption laid the groundwork for serious misgivings. Most importantly, it meant that the de-Baathification regime was built on the presumption of collectivized guilt rather than the presumption of innocence. The Arab Socialist Baath Party, rather than the accusation of human rights violations that had been committed at the executive level, was demonized, which led to significant social strife and political turmoil.

The de-Baathification policies were used to legitimize the assassination of more than 150,000 innocent Iraqi civilians based on the accusation that they were members of the Baath Party. Thousands of others were forced to leave Iraq due to continuous threats and intimidation. The process also failed to take into account the need to maintain a functioning civil service, which had disastrous effects on public ministries that saw over services such as education and health. While the de-Baathification policies were officially targeting a political party it was the civilian population that ultimately paid the highest price.

In many ways, the de-Baathification process was nothing else than a purge. The framework and legal powers of the de-Baathification scheme were opaque, lacked meaningful oversight and accountability mechanisms, and violated basic due process and human rights standards. Even when power was given over to the Iraqi Governing Council (IGC) in September 2003, the de-Baathification measures continued and intensifies under the Higher National De-Ba’athification Commission (HNDC), and were subsequently also introduced into the permanent Iraqi constitution.

The mass killing and dismissal of alleged Baathists that had commenced in 2003 only subsided in 2008 when the Accountability and Justice Act was passed. While this bill sought to stymie the de-Baathification process and review the results, little reflection came to fruition and the law, like its predecessor, was ultimately employed primarily as a means to weaken the government’s opponents.

The disastrous effects of the de-Ba’athification policies put in place by the U.S. in Iraq following the invasion must not be underestimated. The Chilcot report, issued on the 6th of July 2016, points out that “the increasing codification of the extent of de-Baathification, in the Transitional Administrative Law and then the Iraqi Constitution, was one crucial way in which sectarianism was legitimised in Iraqi political culture, helping to create an unstable foundation for future Iraqi governments.” Indeed, the Inquiry concludes by noting that the early decisions on the form of de Baathification and its implementation had a significant and lasting negative impact on Iraq.

Latest developments in the Iraqi legislature and key articles of concern

On Saturday, July 30, 2016, the Iraqi Parliament officially passed a new bill banning the Arab Socialist Baath Party from any activity across the country. More specifically, Article 4(1) of said law prevents “the Arab Socialist Baath Party from exercising any political or cultural or intellectual or social activity under any name and by any means of communication or media”.

According to the text, “This decree includes other parties who have similar ideas and political messages to the Baath party.” And, in regards to the classification of “a Baathist”, Article 5 provides that the ban on the Party and its members include acts such as (1) “belonging to the Baath Party under any name whatsoever”; … (3) “engaging in any political or intellectual activity that would encourage or promote or glorify the ideas of the Baath Party or membership with that group”; … (5) using any audio-visual media or print to spread the ideas and opinions of the Baath Party; … and (7) “participating in any rallies or demonstrations or sit-ins”.

Moreover, Article 8 also states that anybody caught “becoming a member of the outlawed Baath Party or promoting the ideas and opinions by any means” will be put in jail for up to ten years, and Article 9 provides that anyone who is caught “contributing or helping through the media to publish thoughts and opinions of the Baath Party” shall be punished by imprisonment “for a term of no less than six years.”

Undermining political freedom, the precedent for legal abuse and the polarization of Iraqi society

Iraq is a party to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). By enacting this new bill, the Iraqi government is actively in violation of its international obligations under this Covenant and other obligations under international human rights law.

GICJ is very concerned with this blanket ban on Baathism as it runs counter to well-developed principles of international human rights law and undermines the inherent dignity of the human person. In particular, the new Iraqi law is in clear violation of several articles of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) which seeks to protect the enjoyment of civil and political freedom as well as freedom from fear.

In accordance with Article 19 of said treaty, (1) “everyone shall have the right to hold opinions without interference” and (2) “everyone shall have the right to freedom of expression” including “the freedom to seek, receive and impart information of all kinds, regardless of frontiers, either orally, in writing or in print, in the form of art, or through any other media of his choice”. Article 5 of the new Iraqi law is in clear and unquestionable violation of these international legal principles.

Article 26 of the ICCPR further provides that “the law shall prohibit any discrimination and guarantee to all persons equal and effective protection against discrimination on any ground such as … political or other opinion.” GICJ is highly concerned that the new Iraqi law indeed legitimizes the discrimination of individuals based on their political stance or societal opinion.

Moreover, Article 21 and 22 of ICCPR, which provides for the “right of peaceful assembly” and “the right to freedom of association with others”, respectively, are blatantly violated by the new Iraqi ban on “participating in any rallies or demonstrations or sit-ins” (Article 5.7).

GICJ is also gravely concerned about the highly ambiguous legal language employed in the article outlining the definitional requirements for “Baathists”. Such imprecise and wide-ranging classification leaves much room for legal abuse. GICJ has received numerous letters, emails and instant messages from Iraqi civil society and the general citizenry expressing their fears that this new law can and will be applied maliciously. Echoing these sentiments, GICJ is highly concerned that the newly enacted law may be used as a pretext by the Iraqi government to pursue political opponents as has been documented to be the case with the application of the Anti-Terrorism Law No. 13.

In the cases drawing upon Anti-Terrorism Law 13, the Iraqi government has systematically refused to provide any information as to the individuals charged, the alleged crimes, or the legal proceedings. As such, there is a great chance that such a position will characterize the application of the new anti-Baathist law as well. This, in turn, means that the new law could well be used to publically legitimize otherwise illegal sentences of years and even lifetimes of imprisonment.

In this regard, GICJ would also like to note the fact that the Iraqi judiciary does not uphold the basic rights and obligations in regards to fair trial and due process, and has been known to base prosecutions on forced and faulty confessions. Numerous GICJ sources have also repeatedly documented that the judiciary prevents those prosecuted from amounting a satisfactory defence.

Lastly, GICJ would also like to stress the very real political and social effects that the law passed by the Iraqi Parliament will have on Iraqi society. In particular, GICJ is concerned that the illegalization and alienation of the Baathist party (and all other political sentiment that even remotely resembles it) fuels sectarianism and leads to greater political and social polarization in the country, as was clearly the result in the years following the introduction of the de-Baathification measures in 2003.

This continuation of political revenge will not foster positive change or development in Iraq but add fuel to hatred and violence. There is no doubt that criminal justice is crucial for the future empowerment of Iraqi society, but in echoing the sentiment of UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Zeid Ra’ad Al-Hussein in his speech on the 1st of August 2016, let us remember that “vengeance is not justice”.

Recommendations

In light of these concerns, Geneva International Centre for Justice (GICJ) recommends the following:

- Urges the international community, and especially the relevant United Nations bodies and mechanisms, to exert pressure upon the Iraqi government to repeal this new law that contravenes international human rights in order for the state of Iraq to bring its domestic legislation in line with its international commitments.

- Calls upon the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights to denounce this new violation to Iraqi obligations under international human rights law, and to urge the government to put an end to the enactment of measures that promote hatred and divisions within the Iraqi society instead of reconciliation and peace.

- Recommends that the UN Special Rapporteur on the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and of association include the issue of this new law into his next report.

- Recommends that the UN Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers carefully monitor this new law and include the topic into his next report.

- Urges the United Nations human rights bodies, and especially the High Commissioner for Human Rights, to investigate all violations of international human rights law that occurred in Iraq since 2003 throughout the De-Baathification measures.

Documenting and reporting human rights violations in Iraq

| Executions | Human Rights Violations in the context of fight against terrorism | Peaceful protests | ||||

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

||||