By Aimara Pujadas Clavel / GICJ

Myanmar's Rohingya Muslim community is victim of a genocide, massively fleeing to neighboring country Bangladesh. Bangladesh is now in need of assistance from the international community in order to provide dignified living conditions to the refugee population. On Friday 12th February 2021, the Human Rights Council convened a special session to address ‘the human rights implications of the crisis in Myanmar’. This request, jointly submitted by the Permanent Mission of the United Kingdom and the Permanent Delegation of the European Union, was officially supported by 19 member States and 28 Observer States[1].

This is the third special session convened by the Council specifically addressing the human rights situation of the country. Previous sessions have addressed the violent repression of civilians by the government of Myanmar following peaceful protests; and allegations of systematic violations in Myanmar. The Rohingya Muslim community is the world’s largest stateless population, with no legal claims to citizenship in Myanmar, their country of origin.

As we must recall, Rohingyas were not a stateless community throughout the history of this country, in fact, they were recognized as eligible for citizenship in the first citizenship law of 1948 after independence, had voting rights, and Parliamentary members were elected from the community. However, after General Ne Win’s military coup in 1962, the military junta started a series of military campaigns against people of Indian, Chinese and Pakistani origin that turned into a “nationwide immigration and residence check”. In 1982, the Citizenship Act was passed and the Rohingyas were denied citizenship rights; a law that drastically changed the direction of the politics that had, until that moment, accommodated ethnic groups in the country and ensured their participation in Myanmar´s sociopolitical life.

Discrimination and exclusion against minority groups became the hallmark of the laws and policies of Myanmar for over half a century, consequently exacerbating internal conflicts during which serious violations of human rights and international humanitarian law, including airstrikes, shelling of civilian areas, and the destruction and burning of villages; took place.

The Rohingya refugee crisis, resulting from the systematic state-ordered atrocities conducted towards this community, led to a massive wave of forced migration to neighboring country Bangladesh. Subsequently, the recent mission of Tom Andrews, the UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar, was conducted from 13th to 19th December 2021 in Bangladesh, the country that hosts most of Rohingya refugees.

The Special Rapporteur declared: “Bangladesh saved untold numbers of lives when it opened its arms and hearts to Rohingya people who survived these most unspeakable of horrors inflicted on them by the Myanmar military”. On this sense, he thanked Bangladesh for providing protection to Rohingyas since 2017, when they were literally running for their lives from the Myanmar military’s genocidal attacks against them; and urged the international community to take responsibility and act in partnership with Bangladesh in order to offer stronger, sustained financial and technical support.

As stated by the UN Special Rapporteur, “we all have a responsibility to respond to genocide and mass atrocity crimes and to help and support the Rohingya. Bangladesh cannot and should not bear this responsibility alone”.

During the visit, Andrews held meetings with individuals with diverse experiences and perspectives, from Ministers and senior officials, to Rohingya refugees living in camps in Kutupalong and on Bhasan Char. A consistent finding was the critical issue of security and protection, which is exemplified by the recent murder of Rohingya activist and leader and human rights defender, MohibUllah[2], assassinated on 29 September 2021 in his office in the Kutapalong camp in Bangladesh.

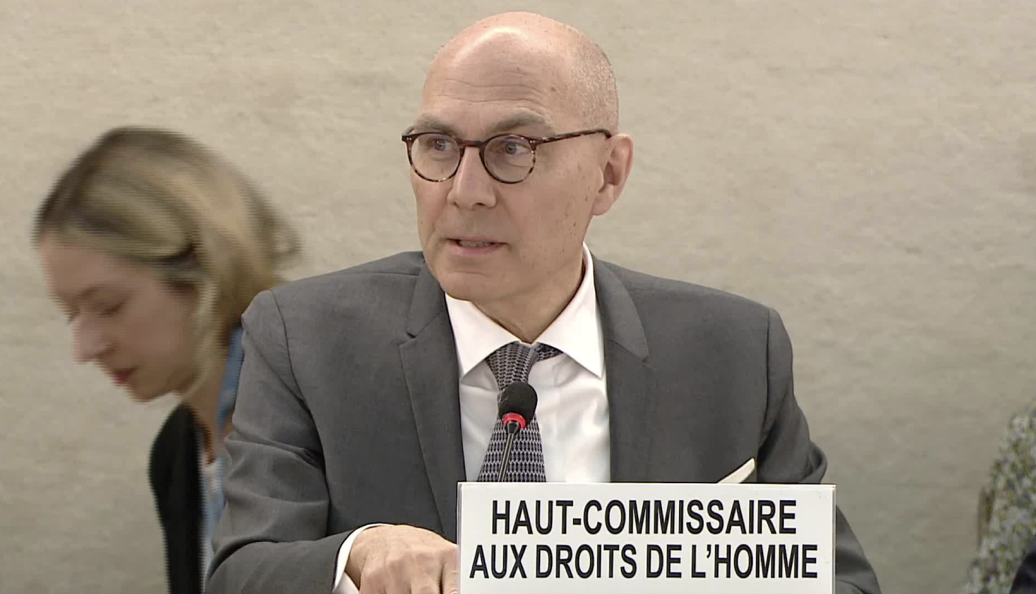

As noted by Michelle Bachelet, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights: “the ongoing armed conflict in Rakhine, which is affecting all communities, combined with the absence of a conducive environment for a voluntary, safe, dignified and sustainable return, have further exacerbated the Rohingyas’ vulnerability”, therefore, it is peremptory that Myanmar’s Government take immediate steps to address this chronic situation, including by amending the 1982 Citizenship Law and restoring Rohingya citizenship.

Geneva International Center for Justice (GICJ) reiterates its warnings against the ongoing genocide of Rohingya people in Myanmar, a genocide which requires immediate international action. GICJ calls on the international community to pressure Myanmar’s government to protect and respect the rights of members of ethnic minorities, notably by ensuring accountability for crimes committed under its jurisdiction, and resolving the conditions that led to mass displacement. Furthermore, GICJ encourages international support for the hosting of Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh, to ensure that their rights are respected.

[1] The UN Commission of Human Rights, created in 1946 to examine and monitor major human rights violations, was initially the body in charge of reviewing the human rights situation in Myanmar prior to the establishment of the Human Rights Council in 2006. The Commission adopted resolution 1992/58 establishing the mandate of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar, which has been extended annually since 1992.

[2] MohibUllah was also the chairperson of Arakan Rohingya Society for Peace & Human Rights (ARSPH). He documented various atrocities committed against the Rohingyas by Myanmar’s military and advocated for the rights and recognition of Rohingya refugees at the United Nations Human Rights Council and several other international platforms. In August 2019, he organised a large peaceful rally to mark the second anniversary of the military crackdown on Rohingyas in Myanmar, in which many Rohingya refugees participated in.

Justice, Human rights, Geneva, geneva4justice, GICJ, Geneva International Centre For Justice