30.04.2018

By: Mutua K. Kobia

During my lifetime I have dedicated myself to this struggle of the African people. I have fought against white domination, and I have fought against black domination. I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunities. It is an ideal which I hope to live for and to achieve. But if needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.

Remarking that 2018 marks the seventieth and twenty-fifth anniversaries of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action (VDPA) respectively.

In light of the Declaration on the Centenary of Nelson Mandela, made by the Assembly of the African Union at its thirtieth ordinary session, and the decision of the Assembly at its twenty-second ordinary session to declare 2014–2024 the Madiba Nelson Mandela Decade of Reconciliation in Africa; the Human Rights Council at its 37th Session adopted a resolution (37/15) to hold a high-level intersessional discussion celebrating the centenary of Nelson Mandela on the 27th of April, 2018.

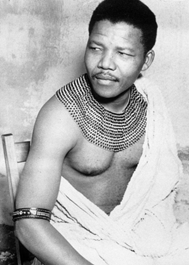

Background of the life and career of Nelson Mandela

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela was born on 18 July, 1918 in Mvezo South Africa and was the son of Chief Henry Mandela of the Madiba Clan of the Xhosa-speaking Tembu people. at an early age he dropped his chieftainship to become a lawyer – this already was the beginning of his pursuit for justice. He was an activist at the University of Fort Hare and would later establish a law firm in Johannesburg in 1952 with fellow lawyer and activist Oliver Tambo. From the early 50s blacks in South Africa were becoming more and more oppressed and slowly losing more and more rights to a government of white superiority that would eventually enforce apartheid rule.

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela was born on 18 July, 1918 in Mvezo South Africa and was the son of Chief Henry Mandela of the Madiba Clan of the Xhosa-speaking Tembu people. at an early age he dropped his chieftainship to become a lawyer – this already was the beginning of his pursuit for justice. He was an activist at the University of Fort Hare and would later establish a law firm in Johannesburg in 1952 with fellow lawyer and activist Oliver Tambo. From the early 50s blacks in South Africa were becoming more and more oppressed and slowly losing more and more rights to a government of white superiority that would eventually enforce apartheid rule.

Nelson Mandela along with other activists would lead the fight against apartheid rule, oppression against blacks, and the equal rights for all people in South Africa, particularly via the African National Congress (ANC) and later the Umkhonto we Sizwe (‘Spear of the Nation’). However, the South African government at the time not only stripped people of their political and social rights but also legally allowed police forces to use violence against any opposition to their rule.

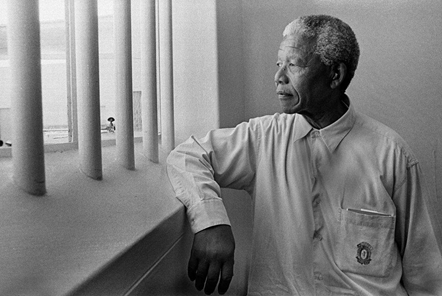

Mandela was eventually arrested for his participation and leadership in fighting the discriminatory practices and laws of the government and essentially for attempting to establish equal political and social rights between blacks and whites in South Africa. He would spend 27 years in prison before being released by a much more tolerant and civil government led by F.W. De Klerk who would release Mandela in 1990. Nelson Mandela would then become the first black president of South Africa in 1994. After serving one term as President he continued to be a global ambassador for equal rights and even served as a mediator of peace.

Nelson Mandela passed on 5 December 2013 at the age of 95 and is heralded as one of the greatest and revolutionary political leaders the world has seen.

“For to be free is not merely to cast off one's chains, but to live in a way that respects and enhances the freedom of others.” – Nelson Mandela 1918 – 2013

Apartheid Rule in South Africa Leads to a Radical Nelson Mandela

In 1912 the African National Congress (ANC) was founded with the aim of creating a democratic and non-racial South Africa – this was to be achieved by combating white minority rule, which sought to oppress, in particular black South Africans. Nelson Mandela would join the ANC in 1943 and subsequently form the Youth League of the Congress along with Oliver Tambo and Walter Sisulu who were already partners with Mandela for several years. Both leagues were dedicated to uniting black Africans and improving their conditions, fighting racism, and ensuring equal rights through the philosophy of non-violence.

It is important to note this aspect of Nelson Mandela’s legacy as it demonstrated his commitment towards equality through the concept and action of non-violence. However, the South African government at that time believed that whites were superior to blacks, and therefore, must rule over them. To ensure effective rule the Government slowly but steadily stripped social and political rights from black South Africans. As the ANC and Nelson Mandela continuously advocated equal rights by holding protests and opposing a racially discriminatory Government so did the Government resort to harsher means – the most severe and evil form of oppression came by way of the apartheid system.

In the late 40s and early 50s the ANC and its Youth League participated in protests, boycotts, rallies, strikes, and other actions of peace against civil disobedience and especially racism and racial discrimination. However, as the discrimination and brutal policing became even harsher Mandela and the ANC Youth League become more radical to the point where Mandela even considered non-violence as a “useless strategy”.

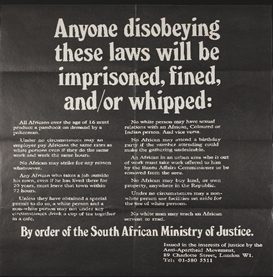

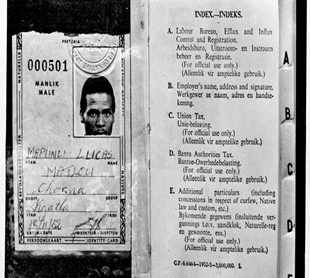

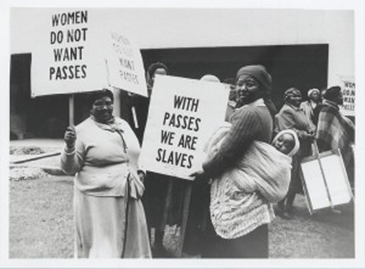

Apartheid rule became a bitter reality in 1948 when the National Party brought apartheid laws into practice by a whites-only election. The National Party supported white supremacy and introduced laws that would tighten and increase segregation between blacks and whites in all walks of social life and would also intensify discrimination against blacks. Children were forced to go to different schools, and blacks could not sit at same table in a restaurant with fellow whites, they could not marry with each other, or even sit together in a bus. In due time South Africa went from “petty apartheid” (all walks of life) to “grand apartheid” (physical separation of racial groups in cities and countryside)1. In 1955 Mandela helped draft the Freedom Charter. “most important document political document ever adopted by the ANC” (Rivonia trial manifesto). In 1958 an even more oppressive government took power and enforced the requirement for black men and women to carry passes in order to enter white-only areas. In response to the discriminatory passes anti-passing campaigns were launched by the ANC and other rival protest groups2.

|

Legalized racial discrimination |

A copy of a "pass" |

|

Social segregation in South Africa |

South African women protesting against "passes" |

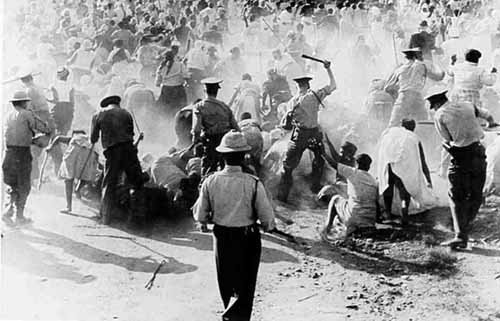

Sharpeville massacre:

On March 21, 1960 an anti-pass demonstration against apartheid and particularly for the abolition of South Africa’s “pass laws” took place where 69 protestors were shot dead (most in the back) and over 180 others were injured by police when they showed up to a police station without a “pass”. Organized by PAC thousands of unarmed blacks protested outside a police station and invited arrests by presenting themselves without passes. A similar demonstration in the Western Cape Township, Langa, was also met with violent clashes with the police as they killed 3 people and injured 27 others. Allegedly the protestors began burning their reference books in front of the police, which provoked the police to open fire into the crowd.

Following these events, it was concluded by the leaders of ANC and their white sympathizers and supporters that non-violent means alone were not be able to overcome apartheid rule in South Africa. It should also be noted that despite South Africa’s growing economy, Indians, Coloureds, and in particular blacks lived in widespread poverty and harsh conditions such as malnutrition and disease due to the discriminatory and racist laws and treatment enacted on people who were not white – all this while whites lived well.

The results of the brutal violence in Sharpesville and Langa, including the oppressive developments against non-whites in the late 50s and early 60s in South Africa became a turning point for Nelson Mandela and led him and others to believe that their strategies and tactics of non-violence and passive resistance to bring about meaningful political changes were clearly not working. As the government of South Africa became more and more oppressive by effectively suppressing the ANC, enacting laws of segregation, the authority for police officers to use torture and other violent and atrocious acts including killings against any opposition towards the government, and stripping black South Africans of the right to vote, blacks in South Africa became ever more disenfranchised. The oppression and injustice increased and so did the rebellion against racism and racial discrimination to attain equal rights for people in South Africa.

"If the government reaction is to crush by naked force our non-violent struggle we will have to reconsider our tactics. In my mind we are closing a chapter on this question of a non-violent policy." Nelson Mandela to reporters when he left the country in 1962

Thus, on 16 December 1961 (same day in 1838 that the Afrikaners defeated the Zulu at the Battle of the Blood River), the ANC along with other organisations launched Umkhonto we Sizwe (“Spear of the Nation”/’MK’) upon a proposal by Mandela. As oppression against black South Africans grew Nelson Mandela and others resorted to “bombing government property and sabotaging power plants” while causing minimum risk to civilians in an effort to hinder the government’s oppression of black South Africans. Instructions were to “avoid attacks that would lead to injury or loss of life.”

27 long years in prison for opposing white-minority apartheid

“South Africa belongs to all who live in it, black or white, and no Government can justly claim authority unless it is based on the will of the people.” – The Freedom Charter

In 1962 Nelson Mandela was arrested for leaving the country without a passport and for inciting a workers’ strikes and subsequently sentenced to five years in prison. As he was imprisoned for political offenses evidence of his activities with Umkhonto we Sizwe such as sabotage plans were brought up, which then added to his previous charges and eventually led to a two year trial.

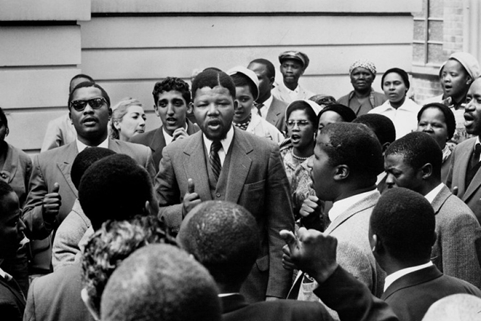

Rivonia trial

The Rivonia Trial immediately became a popular and very significant trial for Nelson Mandela and the struggle against apartheid to achieve equal rights for all humans. The trial took place at the Palace of Justice in Pretoria, South Africa between 9 October 1963 and 12 June 1964 – it is called the Rivonia Trial after Rivonia, a suburb of Johannesburg where the leaders were arrested at Liliesleaf Farm, which was used as a hideout for the ANC.

Nelson Mandela and nine others were tried for:

| • Charge One: alleges that they are guilty of sabotage in that they had recruited people for training in the manufacture and use of explosives for the purposes of committing acts of violence and destruction; also the act of warfare, including guerrilla warfare, and military training generally - for the purpose of causing a violent revolution. Furthermore that they had committed 153 acts of sabotage. • Charge Two: the same as Charge One and further recruitment and further acts of violence similar to those listed - but adds a charge of conspiracy to commit acts of guerrilla warfare, acts of assistance to foreign invading forces and acts of participation in violent revolution within the country. • Charge Three: a contravention of the Suppression of Communism Act, lists the commission of the same acts listed in Charge Two. • Charge Four: a contravention of the Criminal Law Amendment Act, alleges the accused solicited, received and paid out money for the purpose of committing sabotage in support of a campaign against some of the country's laws. |

Police raids at the underground headquarters of ‘MK’ discovered arms and bombing equipment. Mandela revealed the truth regarding some of the charges against him. His defense, however, was the famous “I am prepared to die” speech, which was a manifesto of the anti-apartheid movement where Mandela justified his defying the law as he maintaining and demonstrating that they were draconian in a court he called “illegitimate”.

He also underlined the reasons for resorting to violence noting that non-violence and peaceful means towards equality brought further injustices and fewer rights for non-whites. He noted several instances where the practice of non-violence and peaceful protests were met with violence.

“At the beginning of June 1961, after a long and anxious assessment of the South African situation, I, and some colleagues, came to the conclusion that as violence in this country was inevitable, it would be unrealistic and wrong for African leaders to continue preaching peace and non-violence at a time when the Government met our peaceful demands with force.”

| We of Umkhonto we Sizwe have always sought to achieve liberation without bloodshed and civil clash. |

The use of violence by the South African government and the abuse of power and the law to strip black South Africans of their rights and ensure further oppression is what led to the creation of Umkhonto we Sizwe argued Mandela. He further explained that there are four possible methods of violence; sabotage, terrorism, guerrilla warfare, and open revolution; they logically chose the first method as it did not involve the loss of life. He further explained that their attacks were planned and “without bloodshed and civil clash” – instead, they targeted the economic life lines of the country in an attempt to get the voters to rethink their positions; additionally, they sabotaged “Government buildings and other symbols of apartheid” that would additionally inspire those against apartheid and to show the oppressors that the oppressed could retaliate Government violence. If mass action was to be taken against apartheid, Mandela argued, it would rouse other countries to pressure the South African Government.

| Umkhonto was to perform sabotage, and strict instructions were given to its members right from the start, that on no account were they to injure or kill people in planning or carrying out operations. |

Nelson Mandela ensured that the Umkhonto we Sizwe was politically guided by the ANC which had strong values. At the same time he was able to design novel ways of targeting the oppressor in pursuit of liberation and equal rights without bringing violence to any civilian lives.

In his speech Mandela went on to make some important and pertinent distinctions between what Umkhonto weSizwe stood for as well as their objectives and also that of the ANC. He then brought to attention the discrepancies between capitalism and communism. He noted that blacks were more attracted to communism because it did not appear to oppress people based on race or colour of their skin. Blacks and whites under communism could sit and eat together, they could also go to school together, and work together. Furthermore, he made note of the significant economic differences between black South Africans and white South Africans that arose from several factors such as wages and job opportunities. While it is clear that under certain economic and political systems some people can become richer than others he underlined that the laws in South Africa were written to ensure blacks would always remain poor and whites would always remain rich citing the examples of the disparities in education subsidies for black versus white children and the labor market– the concept of equal opportunity is thus completely absent in this system. He also underscored that “The complaint of Africans, however, is not only that they are poor and the whites are rich, but that the laws which are made by the whites are designed to preserve this situation.” In addition to clear, blatant, and unapologetic racial discrimination that lead to grave inequalities legislation was put in place to prevent, specifically blacks, from “altering this imbalance”.

Nelson Mandela’s “I am prepared to die” manifesto brilliantly demonstrates to some degree of detail the detrimental effects of the evil and discriminatory apartheid system as well as the racist laws enacted by the then government of South Africa and in particular the National Party. It also shows the intelligence, wisdom, and bravery of Nelson Mandela to commit his life-work and career towards achieving equality among all humans and promoting the rights of black South Africans. He clearly put his life at risk several times and would accept the consequences even if it meant life in prison or even death.

The Trial ended on 12 June 1964 and Mandela narrowly escaped the death penalty and is instead sentenced to life in prison. He would spend 18 years in Robben Island prison from 1964 – 1982. In a seven-foot square single cell, the prisoners on Robben Island were prohibited at first from reading material and had to work tirelessly crushing stones with a hammer in a limestone quarry. However, Nelson Mandela’s leadership and rebellion against ill-treatment was put on display as fellow political prisoner, Walter Sisulu, recounted a time when the prison authorities instructed the prisoners to run to the quarry and instead Mandela said, “Comrades let’s be slower than ever”; leading the entire squad it soon became evident that at the pace they were currently taken it would have taken forever to reach the quarry and thus the authorities were compelled to negotiate with Mandela4.

The Trial ended on 12 June 1964 and Mandela narrowly escaped the death penalty and is instead sentenced to life in prison. He would spend 18 years in Robben Island prison from 1964 – 1982. In a seven-foot square single cell, the prisoners on Robben Island were prohibited at first from reading material and had to work tirelessly crushing stones with a hammer in a limestone quarry. However, Nelson Mandela’s leadership and rebellion against ill-treatment was put on display as fellow political prisoner, Walter Sisulu, recounted a time when the prison authorities instructed the prisoners to run to the quarry and instead Mandela said, “Comrades let’s be slower than ever”; leading the entire squad it soon became evident that at the pace they were currently taken it would have taken forever to reach the quarry and thus the authorities were compelled to negotiate with Mandela4.

The ramifications of trial were a continued struggle between those who resisted apartheid (blacks and whites) and the South African Government. Forms of legislation to restrict and even completely deny political activity of blacks in South Africa were passed (e.g. section 6 of Terrorism Act) while a rise in resistance from inside the country with the establishment of youth organisations committed to the struggle. The Durban strikes in 1973 and the student uprising in 1976 led to intensified armed struggle and a growth in MK ranks.

International reactions and Nelson Mandela after Prison

As the trial was seen by the world the international community was able to put pressure on the South African government. For instance, after the trial South Africa was isolated with regards to participation in global sporting events. Could very well have swayed the South African government from using the death penalty.

In 1985, Lord Bethell, a British Conservative Member of Parliament (PM) interviewed Mandela in Pollsmoor, to which he urged the South African government to engage in negotiations and release Mandela. President PW Botha offered Mandela freedom if he renounced the use of violence – but Mandela refused noting that negotiations take place between free people. However, in 1989 FW de Klerk became president and released Nelson Mandela (who was at the time considered a political prisoner instead of terrorist) on 11 February 1990.

In 1990 President F.W. De Klerk ordered the unconditional release of Mandela and on February 11 Nelson Mandela reconciled with the people who jailed him by reaching out to them . Mandela was elected president in 1994 and in his inauguration speech he said;

“We have triumphed in the effort to implant hope in the breasts of the millions of our people. We enter into a covenant that we shall build the society in which all South Africans, both black and white, will be able to walk tall, without any fear in their hearts, assured of their inalienable right to human dignity - a rainbow nation at peace with itself and the world.”

Mandela signed the final draft of the constitution in Sharpeville as a symbolic gesture on 10 December 1996. He retired from presidency in 1999 but still committed himself to conflict resolutions, for instance in Burundi, and in 2010 Mandela would bring the World Cup to South Africa.

Conclusion

Nelson Mandela’s legacy included various actions taken in the struggle to end apartheid and the pursuit of equal rights for all people. His use of legal measures and the establishment of non-violent organisations, most notably the ANC, were testament to his conviction to the lives of people. Mandela, while fighting for the rights of blacks in South Africa at the same time ensured protection and respect for the rights and lives of all people as even when he went to the extent of sabotaging South Africa’s government buildings and economic life lines ensuring that these planned events would not cause bloodshed and civil violence all the while fully knowing that his own life was at risk.

In his manifesto, “I am prepared to die”, he accepted and advocated treason against an unjust, racist, and oppressive government and apartheid system. Nelson Mandela never targeted life and the only life he put at risk for the freedoms of others was his own.

GICJ’s Position

Geneva International Centre for Justice (GICJ) celebrates and promotes the legacy and centenary of Nelson Mandela as well as recognizes the 2014–2024 as the Madiba Nelson Mandela Decade of Reconciliation in Africa. The life and legacy of Nelson Mandela is testament to the will of certain people who commit their lives to the struggle of equal rights. He practiced non-violence resistance, the use of legal measures, and defiance to unjust authority at all costs towards fighting against racism and racial discrimination.

It is with deep regret, however, that despite the recognition of his life struggles racial discrimination persists in 2018. Moreover, a similar system of apartheid is being imposed on Palestinians in the Occupied Territories of Palestine (OPT). However, Nelson Mandela’s legacy is also testament that an apartheid system can be overcome without civil war and without targeting innocent civilians.

GICJ has strongly defended the equal rights of all people and continues to promote social and political equality through the Durban Declaration and Programme of Action (DDPA) that all states must fully implement to fight the evils of racial discrimination. GICJ also encourages the international community to take all necessary steps towards ending any form of racial oppression or discriminatory systems in all regions of the globe.

1. https://www.britannica.com/place/South-Africa/World-War-II#ref480752

2. http://www.umanitoba.ca/cm/vol21/no15/nelsonmandela.html